The Gordian Knot of China’s EV subsidies

Europe’s once proud auto industry is at risk of being undermined by a flood of subsidized electric vehicles from China, and this assault may prove very hard to repel.

In a nutshell

- Automakers in the EU are roiling from China’s subsidized EV exports

- China has made industrial subsidies a ubiquitous policy tool

- Not all member states support the EU’s probe into the issue

In October 2023, the European Commission initiated a probe into subsidized battery electric vehicles from China. In her State of the Union address on September 13, 2023, Commission President Ursula von der Leyen noted that autos priced “artificially low” owing to “huge state subsidies” had been flooding global markets. The probe, which coincides with a surge in China’s electric vehicle (EV) exports to the European Union, is a top agenda item in EU-China relations.

If the investigations substantiate the charge, the Commission may levy countervailing tariffs on EV imports from China to offset state subsidies and level the playing field. The measures would be implemented within 13 months.

This is taking place against the backdrop of the declining competitiveness of Europe’s legacy auto industry and mounting political distrust between Brussels and Beijing. EU policymakers seem to be fed up with China’s mercantilist strategy and are particularly alarmed over its “nationwide mobilization” approach to promoting prioritized industrial sectors.

China’s plan has worked well

Up to now, China’s approach appears to have been working. In a February 2023 report, MIT Technology Review described the situation like this: “Before most people could realize the extent of what was happening, China became a world leader in making and buying EVs. And the momentum hasn’t slowed: In just the past two years, the number of EVs sold annually in the country grew from 1.3 million to a whopping 6.8 million, making 2022 the eighth consecutive year in which China was the world’s largest market for EVs. For comparison, the United States only sold about 800,000 EVs in 2022.”

In 2023, the onslaught has continued.

Facts & figures

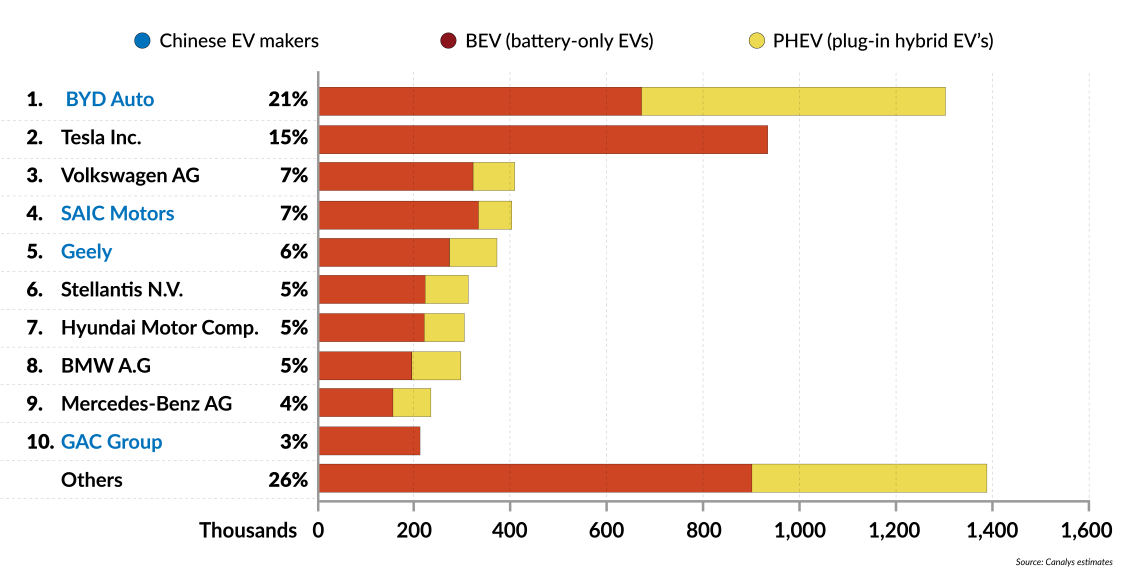

Market shares of top 10 EV makers, first half of 2023

With a total of 3.4 million units shipped to consumers, mainland China, the most substantial EV market, accounted for 55 percent of global EV sales in the first half of 2023. Its growth rate was 43 percent – a far cry from the 118 percent growth recorded in the first half of 2022. The decline has been attributed to the ending of Beijing’s EV support scheme and the Tesla-led “price war,” which weakened the sales of Chinese EV brands.

Taking a shot at fuel-cell vehicles could be more promising, as Chinese firms might be able to leapfrog their Western competitors.

The Father of electric vehicles

In 2006, BMW, one of Germany’s premier automakers, commissioned a comprehensive survey of the fuel-cell vehicle program in China.

That program had been initiated by Wan Gang, an automotive expert who, a decade earlier, had enjoyed a successful career in leadership positions at Audi. Among other endeavors while in Germany, Dr. Wan Gang and his doctoral candidates conducted primary research on fuel-cell technology. In 2000, he wrote a letter to the State Council of China suggesting his native country adopt a bold new strategy for developing its automotive industry.

He argued that the market-for-technology approach – China’s acquisition of Western know-how in exchange for granting foreign firms access to its massive market – had not brought significant progress. Taking a shot at fuel-cell vehicles could be more promising, as Chinese firms might be able to leapfrog their Western competitors.

Read more on Europe’s strategic dilemmas

Europe’s battery strategy

The EU’s new China strategy is stress-tested

Communist Party of China (CCP) officials responded by inviting Dr. Wan Gang to return to China and take charge of research and development for fuel-cell vehicles. They provided him with funding to set up an R&D team at Tongji University. Additionally, the Shanghai automotive industry was mobilized to grant vigorous support to the project. Over time, Dr. Wan Gang became Tongji’s president and eventually China’s minister of science and technology.

Back to the BMW-commissioned report: when the survey was complete, the automaker showed neither much interest in China’s undertaking nor the green energy trend generally. The prevailing thinking among management was that BMW could continue to prosper in China’s market with its offering of traditional upscale vehicles.

As a matter of fact, the entire German auto industry has become used to the “comfortable globalization” of feeding off the Chinese market. Its fear of giving up its combustion-engine car business has remained deeply ingrained despite the recent, loudly announced EV strategies. Today, despite the subsidies issue, the European automotive industry marvels at Chinese automotive products.

Paradoxically, China’s success with EVs has been an unintended outcome of the Wan Gang fuel-cell car project. Fuel cells can be replenished in minutes (typically with hydrogen) in contrast to chemical battery banks, which require several hours to charge fully. However, the technology proved too challenging for the Tongji team to develop at the time. Eventually, China threw its weight behind chemical-battery EVs.

Faux green production

The presumption behind the battery-only car strategy was that it would create an upward demand spiral. As the costs of renewable energy drop and the use of green power becomes widespread, battery electric vehicles increase their market share, further pushing up demand for green energy once they hit the road. But the reality in China 15 years ago was not quite there yet.

China’s “EV Father” was lucky in one respect. His project fit snugly in Beijing’s strategy of mercantilism.

Even now, as China leads the world in solar and wind power generation, the share of renewables in its energy mix remains insignificant. Chinese EVs can hardly be regarded as genuinely green products in that country’s context, from the production chain to use, which initially prompted discussions within the Chinese government. Zhang Guobao, the politically influential former head of the Chinese National Energy Administration, once publicly expressed skepticism about Dr. Wan Gang’s EV pitch. Today, there is also the problem of “EV graves,” the lots filled with thousands of abandoned or never-used older-model EVs – the consequence of local governments’ feverish pursuit of production growth with disregard for consumer demand.

Mercantilism as the state strategy

However, China’s “EV Father” was lucky in one respect. His project fit snugly in Beijing’s strategy of mercantilism, which is the essence of the “Made in China 2025” program and the focus of its five-year plans since 2000. Chinese leadership has recognized electric vehicles as a promising and profitable product for the future.

Beijing has become convinced that Chinese-made EVs can be competitive in the domestic market (and indeed, German cars no longer sell so well in China) and exported in large numbers to the West. Because Western consumers favor green products, such exports could be lucrative. Consequently, the government decided to support EV development through various channels. China’s exports of solar and wind power products had been successfully developed within the same framework.

In the last few decades, the country heavily promoted the use of EVs. China has an enormous population and market, which makes it an ideal proving ground for improving technology. Some local governments have made their public transportation and taxicab systems use EVs across the board – the sort of pressure to adapt unthinkable in a democratic country.

Chinese officials also legally require all automakers to meet specific EV quotas in their production. Since the beginning of the millennium, generations of CCP leaders have consistently followed mercantilist precepts in seeking to develop EVs as a strategic industry. The rapid expansion of 5G telecommunication networks – another CCP-mandated national priority – opened the way for quantum leaps in the digitization of Chinese automobiles. Today, that feature serves as a strong selling point for the country’s EVs.

Components of China’s success

While EVs require fewer mechanical parts than combustion-engine vehicles, there is still plenty of space for innovation. For the past decade, Chinese manufacturers have been putting lithium-iron-phosphate batteries (LFP technology) in their EVs instead of the nickel-manganese-cobalt (NMC) lithium batteries that are more popular in the West. LFP batteries can make EVs cheaper, safer and capable of longer ranges. Listed among the world’s 10 largest EV battery makers, six Chinese companies supply 60 percent of the global market.

A planned Shanghai factory expansion has hit a speed bump, while Tesla cars have been banned in some areas of China.

Another aspect of the EV saga is uniquely Chinese. The ruling cadre of President Xi Jinping (in power since 2012) has radically expanded CCP political control to apply, in critical ways, to China’s private industry as well. As a result, privately held firms are implementing national strategies. State-owned enterprises (SOEs) and private automotive companies such as BYD and Xiaopeng are moving in lockstep to serve the CCP’s mercantilist strategy as they enter Western markets.

Finally, China’s EV production has been an active learning process. To help bring the domestic EV industry to a state-of-the-art level in production and distribution, Beijing courted the American EV pioneer Tesla Inc. and offered it unusually favorable terms (no partnership with a local carmaker was required) for setting up shop in China. Tesla’s Gigafactory opened in Shanghai in December 2019 and quickly became the firm’s most valuable plant, but four years in, the honeymoon with the CCP appears to be over. A planned Shanghai factory expansion has hit a speed bump, while Tesla cars have been banned in some areas of China, ostensibly because their built-in cameras and other electronic components are capable of collecting sensitive data.

National mobilization and industrial strategy

Outside wartime, Western countries do not mount large-scale, cross-sectoral national mobilization policies like China’s. And even if governments dole out subsidies, the scale is not comparable to what China has been practicing. Moreover, Beijing relies on industrial policies to develop promising branches of production and, once they are up and running, to set the goals for them. For the Chinese, the term “subsidy” has always had a nice ring, unlike in the West, where most people at least declare their allegiance to a market-driven system.

Once the direction is set, subsidies from various sources and support from multiple levels of government are taken for granted. China is the only economic power that simultaneously relies on authoritarian-style central planning and market mechanisms to compete with the West.

For China, the European market is vital, as it is the only significant market for EVs outside of the Middle Kingdom.

Its system of subsidizing consists not only of public money pumped into branches of industry the government deems strategic, but also of an artificially cheap manufacturing ecosystem. It features depressed worker wages, affordable but dirty energy (the country continues to use prodigious amounts of coal), below-par social security and harmfully low environmental protection standards. For the EV industry, the system also offers reduced administrative costs, like cheaper license plates for electric cars.

In the past, China’s system of national mobilization succeeded in making it a global leader in high-speed rail systems and solar energy. Now, EVs are poised to become another pillar of the country’s economic might.

Scenarios

The stakes are high for both sides. The Europeans are watching in horror as Chinese EVs begin to flood the continent. In the 2023 Munich motor fair, Europe’s biggest, 41 percent of the exhibitors had headquarters in China. That does not augur well for the future of one of Europe’s most storied industries.

For China, the European market is vital, as it is the only significant market for EVs outside of the Middle Kingdom, given that Americans are somewhat averse to Chinese products (at least for now) and do not care for “green” vehicles as much as European customers do. And China cannot simply turn to other continents like Africa or South America, where there is virtually no demand for EVs.

Most likely: The EU’s probes will bring little fruit

China’s subsidies are so multifaceted that even Beijing may have a hard time calculating them. The EU probe will indeed find untangling the Chinese system a very tall order. Alongside the accounting complexity, there is political distrust, reinforced in recent years by President Xi’s increasingly authoritarian and confrontational governance. And then there is the painful lesson that Europe learned in 2022 from its overdependence on Russian energy.

The EU’s dependence on Chinese-made batteries and other green energy supplies may soon become just as ill-advised. Globally, more than 70 percent of the lithium-ion batteries that entered the market in 2021 were made in China. And Beijing’s control over the renewable sector is now felt throughout the entire supply chain. China produces more than 80 percent of wind turbine components and 97 percent of the silicon wafers used in solar panels. Compounding the problem, Europe relies on China for more than 90 percent of critical rare earth element supplies, gallium and magnesium, and China controls more than half the global capacity for the processing of lithium, cobalt and manganese.

Price competitiveness is also a problem for the EU. Even though Chinese firms sell their vehicles at a premium in Europe compared to the prices they can charge for the same models at home, Europe still cannot compete with China’s EVs in this respect.

However, not all EU member countries are equally keen to see a crackdown on trade with China. The German automotive industry, for example, sells nearly one-third of its output in China, where it also sources many of its critical inputs like batteries.

Moreover, if subsidies are ruled to be a widespread “ecosystem” in China, then Western companies operating there, including the Mercedes-Benz Group or Tesla, logically have been benefiting from them as well (if at a lesser scale than local Chinese companies). That will also complicate the EU’s subsidy investigation.

In the final analysis, Berlin may prove the largest roadblock to the EU’s subsidy intervention. German car companies are very concerned about China’s likely retaliation if the EC imposes high tariffs on its EVs. However, French car companies have a smaller market share in China, so France has naturally become a proponent of the EU investigation.

Most likely, the subsidy probe will give Europe a bit more time to shepherd its own EV producers. Or it may prompt China’s firms to move their EV assembly lines to neighboring countries such as Vietnam. China’s mercantilist attitude will remain, however, unchanged. With time, Chinese EV companies will appear in the EU as investors.

For industry-specific scenarios and bespoke geopolitical intelligence, contact us and we will provide you with more information about our advisory services.