Modi looks inward on trade

The government of India has implemented a protectionist policy on trade, taking measures to boost domestic manufacturing. Yet exports have failed to increase, in part because of red tape and poor logistics.

In a nutshell

- The Modi government has been largely protectionist on global trade

- Prime Minister Modi has curbed imports, hiked tariffs and stalled trade negotiations to protect domestic industry

- Still, exports have failed to increase despite a sharp drop in the value of the rupee, and the current account deficit has widened

- The present policy is unsustainable in the view of many economists

India’s economy is experiencing healthy growth, but not because of trade. The export of goods and services contributed a mere 18.9 percent to India’s gross domestic product (GDP) in 2017, down from a peak of 25.45 percent in 2013.

On September 26, the Indian government announced import curbs on “nonessential” imports, part of a larger strategy to stem a widening current account deficit and a falling rupee. One key reason for the problems is a surging trade imbalance. Even after subtracting oil and gold, two commodity imports partly offset by re-exporting as refined crude and jewelry, the trade deficit jumped to a five-year high in July – an 18.4 percent increase year-on-year.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s government has been largely protectionist on the trade front. He has made boosting India’s manufacturing sector a pillar of his economic program, under the slogan “Make in India.”

Protectionism

Ideologically, his Bharatiya Janata Party leans toward economic nationalism. Under Mr. Modi, this has been combined with a need for quick fixes on job growth and a sympathetic ear to industries claiming unfair competition from Chinese goods. Over the past four years, India has repeatedly hiked goods tariffs and sharply increased its use of protectionist devices such as antidumping duties and minimum import prices. Between 2012 and 2016, India increased the number of antidumping duties it imposed from 35 to 75.

New Delhi has also taken a mercantilist view of trade agreements, judging them solely by how much they contribute to the trade deficit. In contrast to the previous government, which signed over a dozen free trade agreements, the Modi regime has deliberately stalled all trade negotiations. Several partly negotiated agreements are in limbo, including those with the European Union, Australia and Israel. Though publicly saying otherwise, New Delhi also nixed plans to join the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) forum.

India has repeatedly hiked goods tariffs and turned to antidumping duties and minimum import prices.

Soon after it was elected in 2014, Prime Minister Modi’s government drew up a list of nearly 200 products that it believed could be manufactured domestically with some degree of tariff protection. The next year, after Mr. Modi suffered a few local electoral defeats, the government began aggressively erecting trade barriers to help Indian manufacturers.

The government sought to leverage India’s large market for weapons and consumer electronics to increase the domestic manufacture of both, a plan that was largely abandoned as too complicated. But electronics were another story. New Delhi raised tariffs on imported parts, starting with phone components and, most recently, on microwave and television parts.

The policy offered Mr. Modi several gains. It was considered a fast means to create jobs and boost growth, and it won him points with his party’s right wing. Contributions from domestic business to his election coffers have probably risen, one reason why Indian governments often embrace protectionism before elections. Mr. Modi’s aides have dismissed any criticism, noting that India was receiving record amounts of foreign direct investment, which they claimed would automatically improve the country’s trade competitiveness.

The economic benefits of this protectionism have been mixed at best. There has been some increase in the production of electronic products, like mobile phones, but the “Make in India” plan is largely based on assembly: the domestic share of value addition for each phone averages a mere 11 percent. The actual macroeconomic impact has been negligible. World Bank figures show that value-added manufacturing as a share of GDP reached a record low of 15 percent in 2017.

Trading down

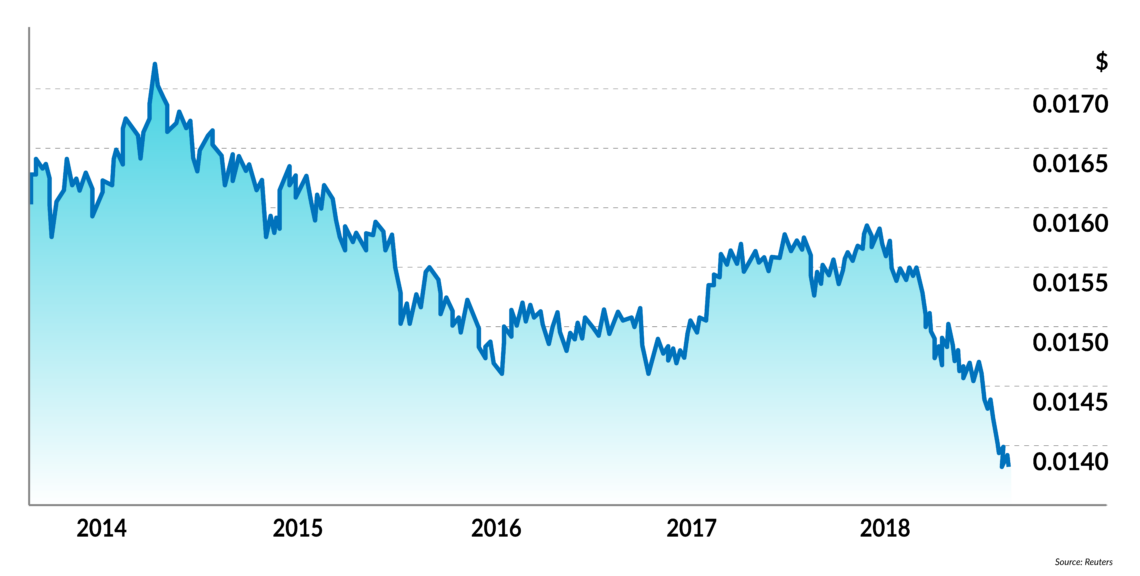

More telling has been that India’s traditionally weak trade performance in goods has continued. Exports failed to increase despite a sharp drop in the value of the rupee, strong evidence of overall noncompetitiveness. The composition of India’s goods exports remains almost the same as four decades ago. Only cars and auto components have been added in recent years.

Facts & figures

Indian rupee against the US dollar

Studies have repeatedly shown that obstacles inside India are to blame. According to an HSBC breakdown of India’s 2008-2014 slump in trade, half is due to domestic obstacles that include red tape and poor logistics. Some of Prime Minister Modi’s reforms, such as a single national sales tax and the digitalization of container transport, should ease these issues, but that will only become clear in two or three years.

India’s poor trade performance is coupled with a larger problem of a widening current account deficit. Accepting that the country’s consumption-driven growth will be import-intensive and that it cannot compensate enough with exports, New Delhi has tried to maintain its capital books by wooing foreign investors and, more recently, by managing the depreciation of the rupee.

That equation is proving harder to balance, as oil prices rise and foreign capital flows ebb due to concerns over emerging markets. The government’s response has been increasingly desperate, including proposed import curbs on luxury goods like high-end electronics and, possibly, automobiles.

Trade mind-set

India’s overall attitude toward trade is flawed. The official view resists the idea that export success is best accomplished by persuading foreign investors to use India as an export hub. The government also rejects the wisdom of an aggressive trade policy geared toward securing overseas market access. Instead, foreign investment is seen as concerning the domestic market. Trade is viewed obsessively in terms of containing an assumed deficit and using tariffs as policy instruments.

The result is that foreign investors in India, seeing an environment primed for import substitution, avoid greenfield manufacturing and limit integrating global supply chains with Indian factories. Indian companies remain too small and risk-averse to go overseas. The Indian firms that are competitive face trade barriers that the import-obsessed commerce ministry fails to negotiate away. Dr. Naushad Forbes, the former president of India’s largest chamber of commerce, wrote in August that the present goal of India’s trade negotiations is “to limit access to the Indian market” when it should be to “increase access to others’ markets.”

Polls indicate that the average Indian feels increasingly positive about trade. A Pew survey in September showed Indians are nearly four times more likely than not to say that trade creates jobs and increases wages.

Even inside the government, there are critical voices. The National Institution for Transforming India (NITI Aayog), the government’s in-house think tank, is particularly vocal. Its first director, trade economist Arvind Panagariya, warned that India would forgo two percentage points of additional growth if it failed to take exports seriously. And Amitabh Kant, the group’s current CEO, has warned that “overprotectionism will create third-class firms.” Most of Mr. Modi’s council of economic advisors are strong free trade advocates.

So far, the Modi government has held to a blend of moderate protection, aversion to trade negotiations and maintaining the status quo. With general elections around the corner, there is little appetite for a major shift in trade policy. The mercantilist rhetoric of United States President Donald Trump has helped legitimize India’s protectionism. Officials now argue that their protectionist stance has been vindicated and that global practices are aligning with those of India.

Scenarios

A growing Indian economy and middle class will suck in imports regardless of whatever the government does to put barriers in place. The present policy is unsustainable in the view of many economists. Without any changes to the present policy, they predict that India’s current account deficit will become a concern every five to seven years. Potentially, if India’s imports become large enough, a full-blown balance of payments crisis could occur as well.

An optimistic long-term scenario says that as the economy grows, India’s corporate sector will become confident and ambitious enough to lobby for access to overseas markets. This is already true in the service and technology sectors, but not in manufacturing and agriculture. Prime Minister Modi’s key economic reforms should eventually increase the profitability and efficiency of the formal manufacturing sector. But the longer this transition takes, the greater the price India will have to pay for market access.

The worst-case scenario assumes a severely negative turn for the world trading system. If the World Trade Organization unravels and governments were to fall back on a network of bilateral trade arrangements, India would be among the least prepared. If the international trading system becomes infected with protectionism, India may find that no one is willing to provide access to their markets. India’s growth story would revolve around a domestic plot and assume a trajectory, as one Indian economics commentator noted, more like Mexico than China.