Globalization: From cooperation to confrontation

Disruptive challenges to the global liberal order are intensifying. The future of globalization will be shaped by factors like climate change, protectionism, public debt and resource scarcities.

In a nutshell

- Globalization is being reshaped by dynamics in trade and geopolitics

- Politics is imposing itself on market forces

- Public debt threatens to erode Western power

Globalization is not dead. Its bedrock is still intact: every second, the internet carries massive volumes of data across continents, as global information networks and cell phones deliver the latest news to the most remote corners of our planet. English serves as the global lingua franca, and we all follow the same calendar. Metrication has made units and norms globally compatible (with a few Anglo-Saxon exceptions).

Globalization was expected to accelerate cooperation and even assimilation. Thirty years ago, pundits prophesied the “end of history” – a final triumph of liberalism, democracy and human rights. Such claims reflected a profound ignorance of history and simplistic assumptions about human nature. In disconcerting ways, it was a liberal version of Marxist historicism. These theories neglected fundamental truths about human nature: power rivalries, cultural differences, and most importantly, the fact that significant political forces (as well as most organized religions) eschew democratic processes.

Economic globalization resulted from Bretton Woods institutions and the economic dominance of the United States. In 1960, the U.S. accounted for 40 percent of global gross domestic product (GDP). Today, its share has dropped to 20 percent. The universalist claim for Western values was embedded in American primacy. In 1945, Washington established the rules for global international behavior and went on to enforce them. The unique period of nearly unchallengeable U.S. military superiority is coming to an end, along with its guiding hegemony in global economic and financial institutions. We tend to forget that globalization has had a strong military aspect. Indeed, the deployment of intercontinental ballistic missiles marked the globalization of strategic threats.

Politics and economics

We are experiencing not the breakdown of globalization, but a growing challenge to the liberal norms and values that have sustained it. China and Russia do not wish to reverse globalization; they want to redefine the rules of the game. Norms restrain power. However, all norms originate from power and fade away unless sustained by raw power. Without the policeman and the bailiff, laws and court judgments are merely empty words. We are heading toward a global contest to determine which country is most successful in imposing its vision and values on a globalized world. At stake are the principles of the Westphalian system, under which all states, big or small, enjoy similar sovereignty – that borders are inviolable, and that all wars are outlawed except for self-defense.

Globalization used to be a marketplace where everyone could freely buy and sell. Then it evolved into a race for innovation and dominance in strategic market segments. Now, it is becoming a global battlefield for power, influence and the shaping of minds and ideas. The belief that trade will prevent conflict (since trade thrives in peace) has eroded. Trade is increasingly seen as an instrument for projecting power and constraining political behavior. The hope that trade will facilitate change – “Wandel durch Handel,” the guiding principle for two generations of German Ostpolitik – has collapsed, along with the expectations that underpinned China’s inclusion in the World Trade Organization.

Today we find that managers often prioritize patriotism over profits, frequently collaborating with political agencies. The old distinction that politics is about power while economics is about profit has disappeared. Governments encourage entrepreneurs to invest in strategic segments of emerging global markets to bolster national power. In Russia and China, most businesspeople are nationalists; both countries pursue political strategies in establishing global economic ties. Power is more important to them than profits. In hindsight, the 2016 sale to China of the German firm Kuka, a world leader in robotics, can be regarded as a strategic mistake.

In the future, globalization will be shaped by seven secular trends:

- Debates over climate change

- Protectionism

- Geopolitical choke points

- Rising public debt

- Persistently high inflation

- New scarcities and market strengths

- Migration and demography

Climate change

The goal to limit climate change to 1.5 degrees Celsius by 2100 will likely be overshot by mid-century. The future will see an uneasy balance between mitigation and adaptation. A mismatch between professed objectives and effective action will become obvious. Countries particularly vulnerable to climate change will need to invest in protective measures.

River deltas (in the Ganges, Mekong, Nile, Mississippi, Amazonas, Rio de la Plata and Po, etc.) will gradually be flooded, and deserts will become more arid. Freshwater will become scarce, particularly among riparian states that need water for conflicting purposes (drinking, irrigation, cooling, discharge, transportation and industrial uses). Tensions between collective declarations (e.g., the Paris Goals) and gaps in actual environmental performance will heighten international confrontation. Russia will prioritize its defense industry and its economy, largely ignoring global warming.

Protectionism

Nations will have to balance the efficiency of the international division of labor against the reliability of supply lines. Security comes at the expense of efficiency – but without security, enduring efficiency is impossible. As trade and financial transactions become weaponized, nations will be hesitant to rely too heavily on a single supplier or financial backer. Sanctions against Russia may have some initial effect, but in the long run, they are likely to undermine the unique position that the U.S. dollar has held in international trade since 1945.

Following its military dominance, American economic and financial dominance will give rise to new challenges. Unipolarity was just a fleeting moment. The future is set to be multipolar; the question is which pole (or poles) will form a new center of gravity. The relative power of the U.S. will decline. Russia and China appear poised to form a strong counterweight, with China being the more powerful player (in both soft and hard power) compared to Russia.

Geopolitical choke points

China’s geopolitical position is precarious: as trade with Europe, the Middle East and Africa grows, so does its dependence on the Strait of Malacca. The alternative to that route, the Northeast Passage, is likely unviable as long as war rages in Ukraine. With both sea lanes potentially vulnerable to blockade, the land-based Belt and Road Initiative will take on vital importance for China. This emerging trade route is likely to marginalize Russia and pull countries along this corridor into Beijing’s orbit.

Read more reports by Rudolf G. Adam

Beyond Russia’s war against Ukraine

While Russia and Ukraine (and the U.S.) battle it out, the real winner appears to be China. Beijing will exploit this opportunity to improve its geostrategic position against both superpowers. China will continue to support Russia, but it will ensure that Moscow loses strength and assumes the role of a junior partner, becoming more dependent and compelled to take orders. Russia’s transportation infrastructure traditionally faces west; it will have to construct entirely new pipelines (and expand railway lines) to redirect trade flows toward Asia. Its access to global waterways is shrinking as the Baltic Sea turns into a NATO-dominated area and the routes through the Bosporus and the Straits of Gibraltar expose Russian navigation to NATO surveillance. The two remaining ports – Murmansk, providing access to the Atlantic, and Vladivostok, offering access to the Pacific – will be the two critical points on which Russia will have to rely for global trade lines.

Rising public debt

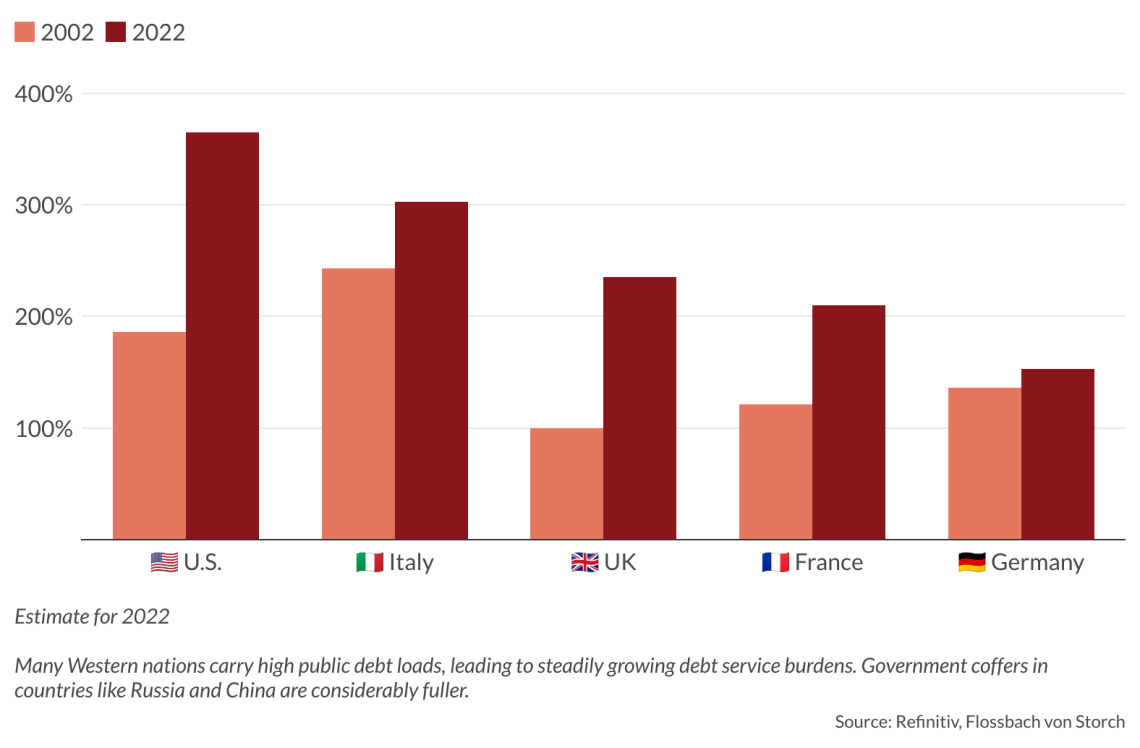

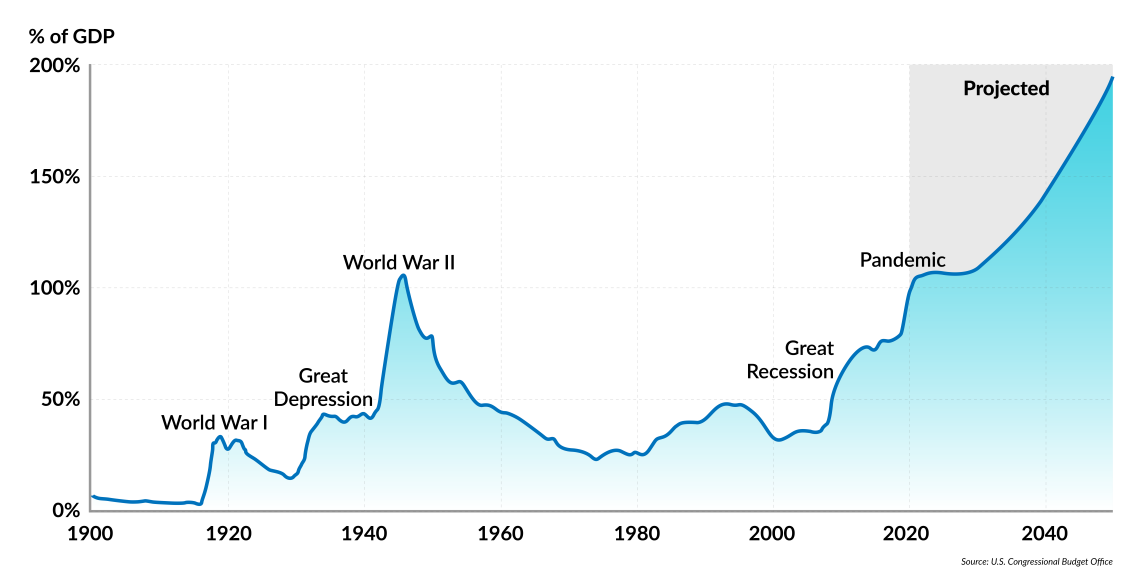

The Western Achilles heel is public debt spiraling out of control. Fifty years ago, public debt over 25 percent of GDP was considered excessive. Today, only eight out of 20 eurozone members adhere to the Stability Pact, which defines upper limits of 3 percent for annual budget deficits and 60 percent for accumulated government debt. When the euro was introduced, these thresholds had to be observed by each member. Germany was among the first offenders, and it is above these limits again. The worst offender in accumulating excessive debt at a dangerous, accelerated pace, however, is the U.S.

Facts & figures

U.S. federal debt held by the public, 1900 to 2050

Most Western nations carry public debt of about 100 percent (Japan holds the record with 226 percent). This results in steadily growing debt service. These figures contrast with the net assets of the governments of Russia and China, which are around $570 billion and $3.13 trillion, respectively (or 32 percent and 17.6 percent of GDP). As the world faces crises of uncertain magnitude and duration, full coffers offer more resilience and more effective power than a massive debt burden.

Facts & figures

Debt in most Western countries is set to grow further. Defense budgets, spending on aging populations, costs for mitigating climate change and adapting to it through preventive structures, new industrial policies, reevaluating supply chains and investing in education, infrastructure and research – all of these are contributing factors, along with ever-increasing handouts, subsidies and stopgap payments.

Inflation

Recent turbulence in financial markets (such as at Silicon Valley Bank and Credit Suisse) demonstrates that central banks must walk a fine line. For years, bankers have complained about zero-interest rates; but as soon as rates rise, banks begin to falter. Higher interest rates place an intolerable burden on highly indebted governments.

Central banks try to strike a delicate balance, ensuring they neither push more banks out of the market nor burden governments with insurmountable debt service costs, while preventing the erosion of nominal bank savings and not stifling economic growth. The myth of central banks’ political independence has been seriously tarnished. Their responsibility has always extended far beyond monetary policy, and their share in overall political responsibility has grown since 2008 – just recall Mario Draghi’s famous promise to do “whatever it takes.”

New scarcities

The oil shocks of 1973 and 1979 should have taught us an enduring lesson about the vulnerability of international supply lines. However, the conclusion that the end of fossil fuels will mean the end of OPEC’s global leverage (and of those, like Russia, who benefit from it) is deceptive.

Electromobility will create new scarcities and dependencies. Demand for lithium is expected to grow by 4,000 percent, for graphite by 2,500 percent, for nickel and cobalt by 2,000 percent and for rare earths by 700 percent. Currently, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) supplies 70 percent of global cobalt and Indonesia 30 percent of global nickel. But production is less of a concern than refining. Globally, China refines 74 percent of cobalt, 68 percent of nickel, 65 percent of rare earths, 59 percent of lithium and 40 percent of copper. Most of these resources can be found and refined in other countries, but at significantly higher production and environmental costs.

Global oil demand prompted the formation of OPEC. There will be a temptation to form a similar cartel for some (or all) of these crucial components of the new age of renewables and electromobility unless industrialized countries begin to mine these minerals themselves. But such efforts will face significant bureaucratic and environmental obstacles. And lithium mining is not a pleasant activity.

There will likely be protests against open-pit mines in densely populated areas. People will campaign vociferously against such environmental degradation. The Serbian government recently revoked its license for Rio Tinto to explore lithium mining at Jadar. Similar problems will arise with copper mines. In Arizona, indigenous tribes have taken legal action against a copper mine at Oak Flat (Chi’chil Bildagoteel) that has the potential to supply a quarter of all U.S. copper needs for almost half a century.

The geopolitical distribution of new essential minerals will grant Australia, African countries (like the DRC, Zambia, South Africa, Equatorial Guinea and Nigeria) and South America additional strategic importance. Access to these minerals could become a much sought-after privilege, requiring a delicate balance of political, economic and financial incentives.

Migration and demography

Changes in the distribution of people across the five inhabitable continents are bound to have the most enduring consequences for the distribution of power and wealth, a subject worthy of its own analysis.

Meanwhile, the concept of free trade is fading. Trade and financial instruments are increasingly taking on political dimensions. International competition is becoming less about who can run faster and more about who is more adroit (and less scrupulous) in tripping up competitors. Business decisions will have to seek greater support, political and otherwise, while considering that sudden conflicts could have disastrous consequences for their global activities.