Mercosur divided

Instead of pushing for more free trade, some members of Mercosur are using it to protect their own industries. The rift may spell the end of the customs union.

In a nutshell

- Mercosur is a flawed customs union, with many trade restrictions

- Some members want more free trade, while others want protectionism

- The bloc could devolve into a simple free-trade area, if trends continue

In March 2021, Mercosur, a South American customs union, celebrated its 30th anniversary. Its name is a portmanteau of the Spanish Mercado Comun del Sur, or southern common market. The organization was created in 1991 by Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay and Uruguay. Inspired by the European Union model, the founders wanted to transform it into a single market that would eventually include all member countries of the Latin American Integration Association (ALADI). However, Mercosur never became a common market, and it remains a flawed customs union, with many exceptions, trade barriers and bureaucratic rules.

Mercosur still comprises only the four founding partners. Venezuela became a full member in 2012 but was suspended in 2016 for failing to comply with the organization’s democratic principles. Bolivia has been engaged in the process of acceding to the bloc as a full member since 2015, but it has not received approval from the Brazilian legislature. For now, it remains an associate member, along with Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Guyana, Peru and Suriname. These countries have trade agreements with Mercosur members, but do not have full voting rights and are not members of the customs union.

Facts & figures

Mercosur members

Today, Mercosur includes more than 295 million people, has a combined gross domestic product (GDP) of about $2 trillion and covers a territory three and a half times larger than the EU.

Mercosur customs rules

Within Mercosur, most customs duties have been eliminated, though some products – notably automobiles and sugar – are still not subject to free trade. In 1995, to consolidate the customs union, Mercosur adopted a common external tariff (CET). Even though the CET has fallen from its original 35 percent to a current average of 13 percent, it is still one of the highest in the world.

Several factors impeded Mercosur countries’ integration into global value chains. Among these are restrictions created by the customs union and a rule requiring that trade agreements with nonmembers be negotiated with the group as a whole, even though the countries do not share a common foreign trade policy. The lack of trade openness was one of the main reasons Mercosur members suffered through decades of low economic growth and stagnant productivity.

It would be better if Mercosur were a genuine free-trade area than a phony customs union.

The Economist

Today, the bloc faces ideological and political polarization, as well as economic hardship aggravated by the pandemic. While Argentina opposes changes, with support from Paraguay, Brazil and Uruguay want more modernization and trade openness. Recently, in a Brexit-like moment, Uruguay announced that it would seek trade deals outside Mercosur by itself, against the customs union’s rules. Brazil, on the other hand, has started unilaterally reducing its import tariffs. Back in 2001, The Economist wrote: that it would be better if Mercosur were “a genuine free-trade area than a phony customs union.” Some 20 years later, the bloc faces the same dilemma.

Integration and protectionism

When Mercosur was created, its stated goal was to promote regional integration and to source most capital goods and economic inputs locally. Brazil and Argentina, however, also wanted to protect their local industries from competition. They rejected the idea of a bigger economic bloc, the Free-Trade Area of the Americas (FTAA), which the U.S. proposed in 1998. The FTAA would have included 34 countries in the Americas and the Caribbean. Negotiations ended in failure a few years later.

Most of Mercosur’s trade deals are with ALADI countries, and only a few of them allow for truly free trade. Outside of ALADI, Mercosur’s sole free trade agreements (FTAs) currently in force are with Israel and Egypt. The group has Preferential Trade Agreements with India and the Southern African Customs Union (SACU), but these cover only a small number of products.

Facts & figures

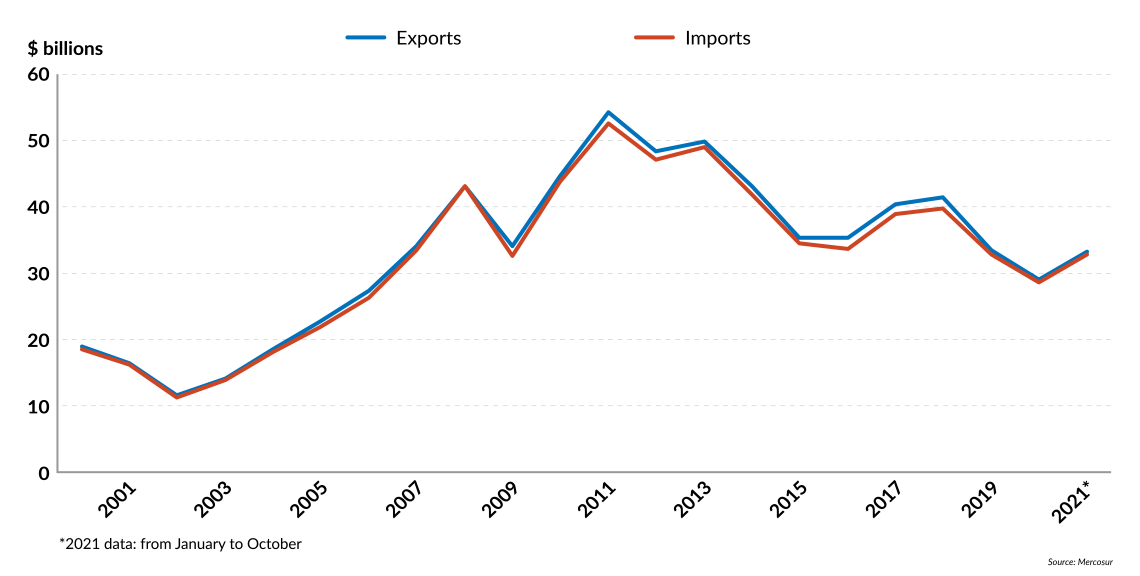

Intra-Mercosur trade, 2000-2021

It took Mercosur 20 years to conclude its biggest and most significant free-trade negotiations – with the European Union – in 2019. However, the agreement has not been officially signed and still must be ratified by the European Parliament and by the parliaments of all of the countries involved. In 2019, Mercosur also concluded negotiations with the European Free Trade Association (EFTA), which includes Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway and Switzerland. But just like its FTA with the EU, the European counterparts are requiring that an additional agreement on environmental commitments be signed.

Brazil is trying to advance Mercosur’s current FTA negotiations with Canada, South Korea, Singapore, the Gulf Cooperation Council, and some other countries, but internal disagreements within the group have slowed down the process. In April 2020, Argentina surprised its Mercosur partners by announcing that it would not participate in any additional FTA negotiations, but soon after signaled a “gradual change in discourse.”

Frustrated with the slow pace of progress, in July Uruguay announced it would start FTA negotiations with China, challenging the customs union’s rules. If the negotiations are successful, Mercosur members will have to decide how to proceed.

Mercosur’s most consequential free-trade agreement, with the European Union, still has not been ratified.

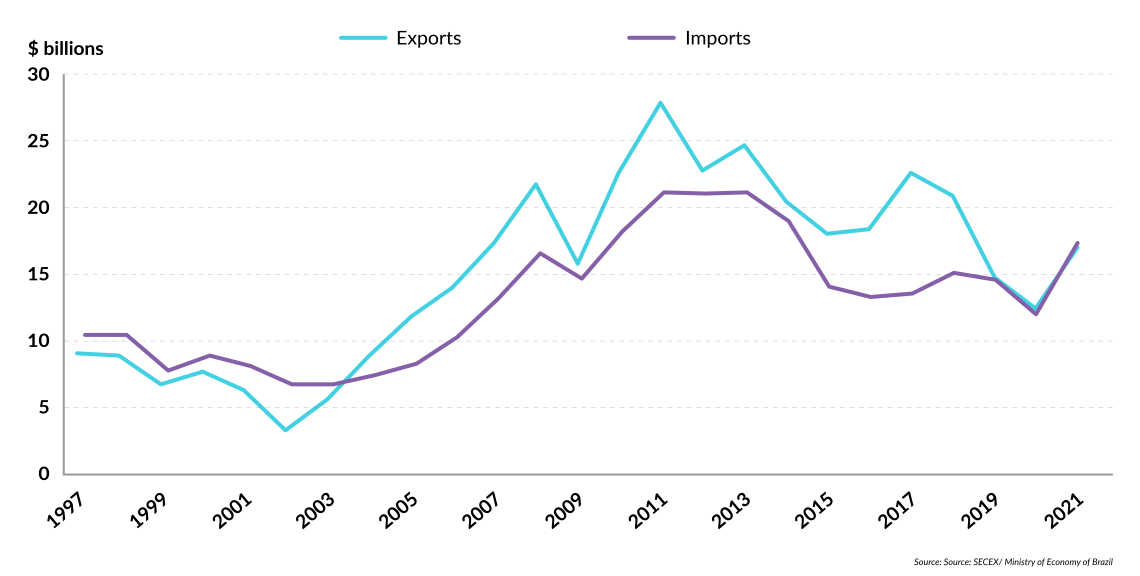

Until a few years ago, Mercosur did not see protectionism as a problem. Intra-Mercosur trade saw robust growth at the beginning of the 1990s, and then again from 2002 to 2011. Since then, however, it has fallen significantly. Mercosur represents only around 14 percent of its members’ total trade. Brazil’s exports to Mercosur last year accounted for only about 6 percent of its global total.

The desire to protect local industry has backfired. A lack of competition brought decades of complacency and low productivity growth. Many factories have not updated their machinery in years – on average, industrial equipment in Brazil is over 20 years old. This in an age when artificial intelligence and 3D printing are becoming increasingly common. Brazil’s industrial production has fallen 20 percent over the past decade. Today, some 70 percent of Brazil’s exports are commodities – mostly agricultural products, metals and oil. These are all products that are purchased primarily by China, and Brazil’s dependence on the Chinese market has become an issue of great concern.

Facts & figures

Brazil-Mercosur trade, 1997-2021

Diplomatic significance

Today, Mercosur is still important as a diplomatic project, but its economic significance has become marginal. A common design for Mercosur passports and car registration plates, as well as the free movement of people (residents of each country need only show their local identification cards when crossing intra-Mercosur borders) have given the bloc a sense of unity. Divisions within the group, however, are bigger than the convergences.

Mercosur’s institutions are nowhere near as developed as the EU’s and have much less decision-making power. The highest decision-making body is the Common Market Council, on which the respective heads of state serve. There is a Mercosur Parliament, but it only serves an advisory role. There is no executive body like the European Commission that is in charge of Mercosur’s policy priorities. That is why Mercosur trade agreement negotiations do not start with a single offer that represents all countries, but with each country offering its own list of products for tariff reduction. The main negotiations then happen within Mercosur itself.

It is common to hear in Brazil that Mercosur has acted as a “drag” on members’ intentions to seek trade openness. The customs union created many limitations and did not even establish free trade between its members. Argentina and Brazil maintain about 100 tariff lines each in the list of exceptions to the CET, Uruguay 225 and Paraguay a whopping 649. The maze of rules of origin and special tariff regimes, lack of regulatory convergence and red tape create other significant barriers.

The customs union created many limitations and did not even establish free trade between its members.

Brazil has been trying to promote policies to modernize Mercosur. Last year, it proposed a 20 percent reduction of the common external tariff but could not get the other members to agree. Instead, it moved unilaterally, reducing its most-favored nation tariffs by 10 percent on about 87 percent of all tariff lines. The reduction is temporary – lasting until the end of 2022 – and Brazil justified the move by saying it was a necessary response to increasing inflation and the economic hardship created by the Covid-19 pandemic. As a legal basis, Brazil cited the 1980 Montevideo Treaty, which allows members of ALADI to adopt measures to foster the protection of human, animal and plant life and health.

During the December 2021 Mercosur summit, members failed to reach a decision on reducing the CET. Argentina, Brazil and Paraguay agreed on a 10 percent reduction, but Uruguay refused to endorse the decision unless it was allowed to negotiate its own unilateral free trade deals outside of Mercosur. The meeting ended in an impasse.

Scenarios

In the short term, it is likely that Mercosur countries will continue to try to reduce the CET by 10 percent. Even if they succeed, however, it will change little. Mercosur’s tariffs would remain among the highest in the world.

Brazil will probably move forward with its unilateral tariff reductions, using all possible exceptions and justifications, but remaining part of Mercosur. It believes it has invested too much in Mercosur’s success to leave the bloc now.

Uruguay will continue trying to find a way to negotiate its own trade deal with China. If and when negotiations are concluded, Uruguay will have to make a choice: Mercosur or China. It is highly unlikely that the other Mercosur members will agree to Uruguay serving as an entry point for Chinese goods and services while it remains a member of the South American customs union.

Longer term, both Brazil and Uruguay will face a difficult choice. To increase competitiveness and break the cycle of low growth, they will need to increase the share of trade in their economic output. In Brazil, trade currently accounts for only about 30 percent of GDP – half the global average. Without an agreement within Mercosur on trade openness, the options will be limited. If Argentina continues opposing changes, it is possible that the others will opt to do away with the customs union and transform Mercosur into a simple free-trade agreement.