East Asia realignment: Japan and the Philippines move closer

Despite historic resentments, the two countries are tightening their relationship. China’s hegemonic ambition has triggered a policy shift among Japan’s neighbors.

In a nutshell

- Tokyo and Manila are today on the best of terms

- Faced with Beijing’s bullying, East Asian states are forging military alliances

- Tokyo shares broader geopolitical concerns beyond its territory

Japan and the Philippines are building a diplomatic rapprochement that could also provide Japan with labor and the Philippines with security, but before examining this strategic development, a quick look at its geopolitical context is in order.

The burden of 20th-century history still haunts the Far East. It most visibly manifests itself in how its nations still labor to come to terms with the legacy of the Empire of Japan that began with the Meiji Restoration in 1848 and formally ended with the enactment of the country’s new constitution in 1947, following Japan’s defeat in World War II.

China leans on the old demon of Japanese imperialism, while relations between Japan and South Korea can be dicey at times. And occasional rhetorical flourishes by Japanese nationalists stir old feelings of resentment in the region.

This background matters as geopolitical pressure mounts on Tokyo to become more involved in the defense of the Western-led international order and help contain the aspiring Chinese superpower. The latest developments in the Philippines-Japan relationship are meant to serve this purpose. Let us begin by looking closer at Japan’s problem.

Japan’s bet on activist foreign policy

Following Japan’s capitulation in 1945, the American occupation and the adoption of a pacifist constitution, the island nation restricted its security strategy to the bubble of its territory, air and sea space. Now, as the world has entered a phase where war is once again “the continuation of policy by other means,” as Prussian general Carl von Clausewitz famously observed, that paradigm is changing. Foreign policy challenges are emerging not only among the region’s smaller nations, but also within the active designs of global powers, including Russia. Tokyo finds itself dealing with both Beijing and Moscow as they are claiming their interests in the Far East.

These days, Tokyo must attend to its geopolitical interests and return, after three generations, to an activist foreign policy.

During the Cold War (1947-1991), the alliances and cross-border military cooperation in East Asia were restricted to the United States. Washington has been Japan’s security provider. The U.S. forces maintain a strong presence in the Western and Central Pacific as the Western superpower strives to contain the Chinese contender. However, the security transaction with Japan is no longer as complete as it was before China’s rise.

These days, Tokyo must attend to its geopolitical interests and return, after three generations, to an activist foreign policy. As a matter of fact, Japan presently understands the global trends better than the former colonial powers of Europe. When it comes to engagement with like-minded countries and to the budgetary, technological and productive hardware of enhanced military power, Japan is advancing faster than the Western European NATO members (the situation is different in the alliance’s northeastern flank, where the member states are beefing up their defenses).

Japan reacted first to the winds of change. Already under the leadership of Prime Minister Shinzo Abe (in office 2006-2007 and 2012-2020), it engaged with significant actors in the Indo-Pacific, notably India, Australia and Indonesia. Even though the new fora and declarations of cooperation are still far from fully-fledged military alliances, Moscow and Beijing have already sounded alarm over an “Asian NATO.”

The Philippines changes sides again

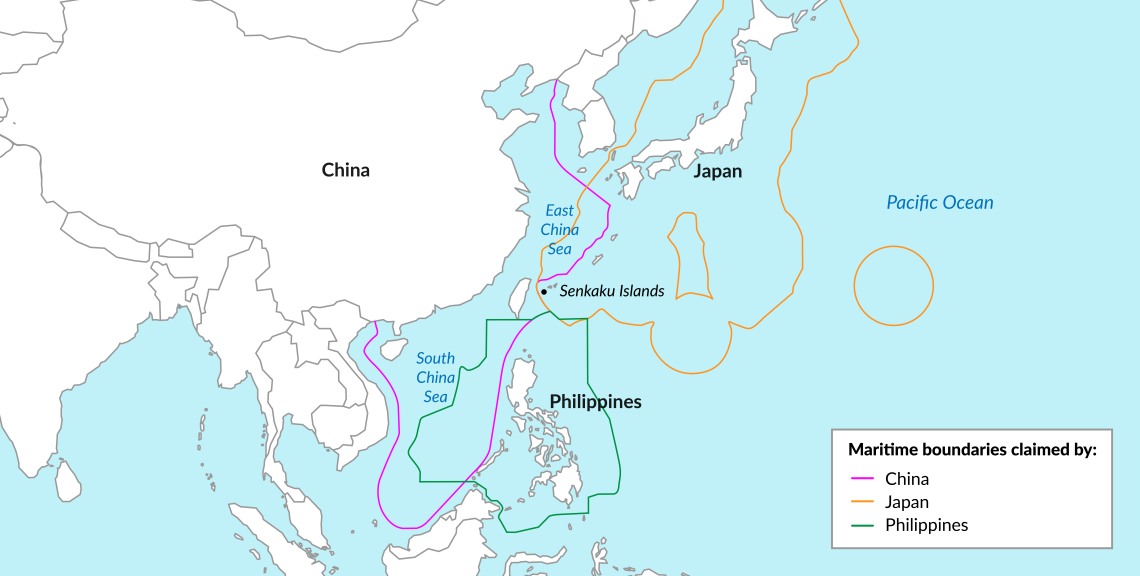

The Philippines is among Japan’s closest neighbors and certainly the most important strategic partner in Southeast Asia. The two countries share maritime borders in the South China Sea, which Beijing claims to be its mare nostrum.

Facts & figures

Long shared history, most of it not happy

The interaction between the two island nations dates to the times of the Spanish colonial empire. The first Spanish Jesuit mission went from Manila to Japan in the middle of the 16th century. The intent to Christianize Japan was to fail, and over time, a substantial group of Japanese traders set up their presence in the Philippines. In 1606-1607, they even led an abortive rebellion against the Spaniards. Relations between the Philippines and Japan were formalized in 1875. Shortly before the end of the 19th century, rumors had it that Tokyo had offered to purchase the Philippines from Madrid.

The most dramatic phase in Philippines-Japan relations occurred in 1898 when Spain sold the entire Philippine archipelago to the United States for $20 million (about $850 million today), and it became an American colony. The Japanese invaded the Philippines following their successful attack on Pearl Harbor, launching the relentless expansion of the Japanese Empire in Southeast Asia and Indochina. Like in many other Japanese occupations, the Japanese troops behaved brutally in the Philippines. More than a million Filipinos lost their lives. In 1942, U.S. forces had to withdraw from the archipelago, only to return three years later. The Philippines gained its independence in 1946.

Beijing’s wide-ranging maritime claims on the South China Sea make it abundantly clear that Manila and Tokyo have common interests that are served by the U.S. containment of China. Both island nations are vital allies of Washington. The U.S. in 2022 called again on China to “conform its maritime claims to international law and to cease its unlawful and coercive activities in the South China Sea.” Most recently, President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. increased the number of American military bases in the Philippines to nine.

Facts & figures

Disputed areas in the South China Sea

The American presence in the Philippine archipelago is more restricted than in the case of Japan, but the two neighbors’ policy responses to the challenges they face are remarkably similar. In 2016, Japan signed a pact with the Philippines to supply military hardware, a move that did not go down well in China. Beijing’s irritation was similar when Japan decided to send weapons to Ukraine after the February 2022 full-scale Russian invasion of that country. Tokyo has been in a decades-long dispute with Moscow over the Kuril Islands, administered by Russia since 1945.

Most significantly, the Philippines recently became the first recipient of Japan’s new Official Security Assistance (OSA), which aims to reinforce the armed forces of like-minded countries. This cooperation is part of Japan’s National Security Strategy (NSS) implemented by Tokyo in 2022 and aims to provide “equipment and assistance for infrastructure development to like-minded countries.” Significantly, the Philippines, a member of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), entered into this agreement shortly after having left the Beijing-sponsored Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), a key pillar of its geopolitical outreach.

Read more on Southeast Asia issues

Once again, Pacific security is Japan’s priority

Beijing’s claims in the South China Sea roil the Philippines

Australia’s foreign policy pivot

Demographic drama and opportunity

For the rapprochement to work well enough, Tokyo and Manila need to extend the policy to the economy: trade, investment and the realm of labor migration. The latter may be particularly promising.

An acute demographic downturn is battering Japan: its population is aging and shrinking rapidly, and industry is desperate for labor. The country cannot fix the problem within its borders. The only practical solution is loosening Japan’s restrictive immigration policy and allowing a controlled inflow of qualified personnel.

If the Japanese are serious about addressing their labor shortage, they have no better country to reach out to than the Philippines.

The labor shortage is acute in the manufacturing sector and services, particularly health and old-age care. Enter the Philippines. Its people are renowned for their cultural adaptability and work ethic; their skills are highly appreciated, including in the nursing services that are in extremely high demand in Japan. Common wisdom in the East has been that Hong Kong would be in trouble without the service inputs of Filipino women. And their home country profits from the remittances sent back home.

If the Japanese are serious about addressing their labor shortage, they have no better country to reach out to than the Philippines. Aside from defense, this is another crucial area where the two sides can benefit from aligning closer.

Scenarios

Three base scenarios for the near future emerge.

Likely: Rapprochement continues

In such a case, expect an increase in the pressure from Beijing, not only on the Philippines but also on Japan. China’s violations of their neighbors’ territorial waters and island grabs have been escalating, which drives the increasing tension. On its own, the Philippine Navy is not able to fend off the provocative actions by Chinese vessels.

Predictably, any extension of Japanese naval support to littoral countries would motivate Beijing to try to lean harder on Tokyo. The Japanese Navy may not focus on the South China Sea but on the disputed Senkaku Islands in the East China Sea. Over there, too, violations of territorial waters by Chinese vessels have been quite brazen. At present, the U.S. strongly supports the Japan-Philippines reproachment and the strengthening of the two allies’ military capacities.

Somewhat likely: Washington shifts its strategy

A second presidency of Donald Trump, possibly beginning in January 2025, could lead to changes in the Japan-Philippines alignment. In his first term, Mr. Trump made it known that under his command, the U.S. might not engage in an open conflict in Southeast Asia – unless U.S. assets are directly attacked. If he is elected and confirms this policy stance, the region’s countries could shift political gears to pursue accommodation with Beijing.

Least likely: Beijing softens course

Under this scenario, Beijing makes a turnaround, seeking the economic benefits that could come from a reduction of tension in the Far East. There have been phases of detente between Japan and China that led to substantial economic benefits to both countries. Most recently, signals are that such a development may occur again. Global economic pressures make it imperative for both China and Japan to search for improved bilateral trade relations. That, in turn, would lead to easing political tensions between the superpowers.

For industry-specific scenarios and bespoke geopolitical intelligence, contact us and we will provide you with more information about our advisory services.